Top Gun: Maverick makes no bones about how indebted it is to 1986’s original Top Gun. Like the first movie, it opens to a montage of fighter jets preparing for takeoff from an aircraft carrier, with familiar synthesizers pulsing on the soundtrack. (“Music by Harold Faltermeyer/Lady Gaga/Hans Zimmer,” reads the opening credits, a compositional A-team never before assembled.) Indeed, Maverick repeats shots, songs, cars, even mustaches from the original.

But I didn’t care about any of that. When I heard that Tom Cruise’s long-gestating Top Gun sequel was finally taking flight, there was only one moment from the original I wanted to see reenacted: the volleyball scene. Would the new film pay tribute to this celebration of sun, sand, and sweat? Would Maverick glisten and flounce as its predecessor did? Yes, I’m happy to say, Maverick does give its characters a chance to do some playin’ with the boys. In fact, Maverick’s beach football scene—like nearly every aspect of this sequel—makes a lot more sense than its corresponding scene did in the original. For most of the movie, making more sense is a blessing. But in this one moment, it’s a shame.

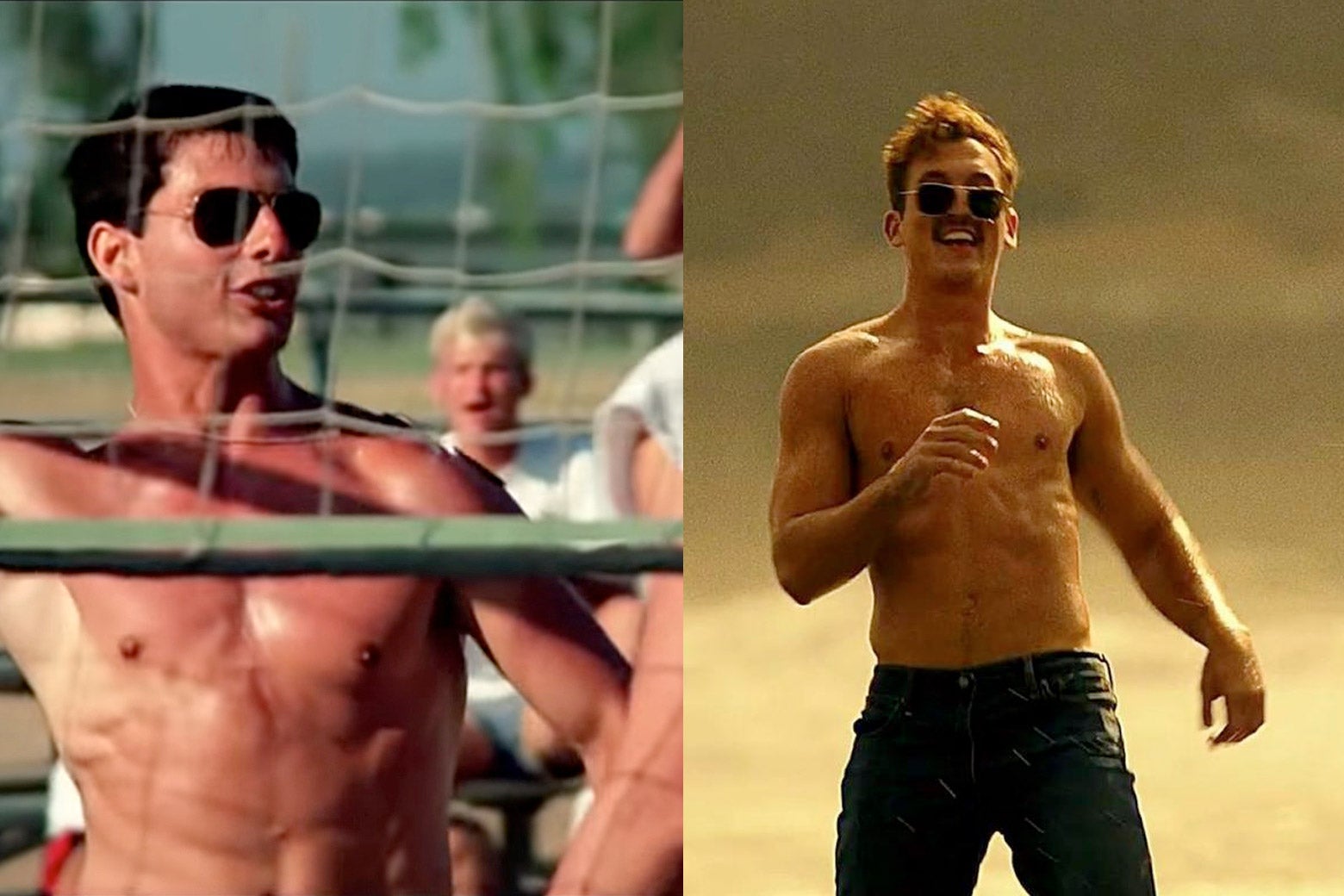

Allow me to explain. The beach volleyball sequence in the original Top Gun was, of course, aesthetically and erotically formative to an entire generation of filmgoers. It’s a command performance of gleaming, intense 1980s masculinity, a 90-second slow-motion showcase for the abs, tans, and attitudes of that movie’s central foursome. Maverick (Cruise) seethes when the ball hits the sand on his side of the net. Anthony Edwards, as Goose, wears a T-shirt and exchanges comradely high-fives—followed always by ritualistic low-fives—with his buddy. Val Kilmer’s Iceman spins the ball nonchalantly on a finger. Rick Rossovich’s insanely sculpted Slider—years later, Rossovich still takes pride that no one matched his physique—strikes a pose worthy of Schwarzenegger.

Whether you dreamed of growing up to be those boys, or you hungered to run your hands along their biceps, or you found yourself confusingly, deliciously in the middle, it was impossible to watch that scene, as a young person in 1986, and not respond with passion and longing. Years later, it’s basically the only thing I remember about a movie I owned on VHS and watched an irresponsible number of times. But why does it work so well?

The foundational legend of the beach volleyball scene is how extraneous it is. The screenplay offered just a few sentences of description about a “vicious volleyball game” on base. The scene makes no attempt to advance the story; the only tie it has to Top Gun’s plot is that Maverick checks his watch a couple of times so the audience doesn’t forget his upcoming date with his flight instructor. The production trucked in a load of sand and hired some stand-ins who actually knew how to play volleyball for the day. In a DVD interview years later, director Tony Scott admitted he found the scene difficult to figure out. “I knew I had to show off all the guys, but I didn’t have a point of view,” he said. “So I just shot the shit out of it.”

Did he ever! If you watch carefully, the sequence does have the flimsiest of arcs: First, Iceman and Slider have the advantage, and Goose consoles Maverick, and then Maverick spikes it past his opponents. But the thrill of competition is not why the scene sticks. It’s not about sports but about bodies in motion. The stand-ins, the ringers, are shot at regular speed (and often from a distance) as they spike, pass, and dig. When Cruise and company are featured, it’s in slow motion, and it hardly matters that they can’t really set a ball. Covered in baby oil, posing before a bright blue sky, they are the purest expressions of Scott’s plan for his beautiful aviators, inspired by photographer Bruce Weber’s 1983 monograph and its photos of sailors on leave.

“I didn’t have a vision of what I was doing other than just doing soft porn,” Scott said of the volleyball scene. That haphazardness creates a loose and silly joy onscreen, a weightlessness at odds with the hard-driving nonsense of the rest of the film. Like Top Gun as a whole, the volleyball scene is not good storytelling; unlike Top Gun as a whole, the volleyball scene delivers its payload.

Three decades later, the actors in Maverick treated their beach football scene as a kind of crucible. They understood that it was this moment—not how snappy their line readings were, not how many enemies their characters shot down—that would be the measure of their achievement. They understood, having seen the impact of the beach volleyball scene, that they were bodies, and that the qualities of their bodies were what mattered. Director Joseph Kosinski has said he’d originally planned for the game to be played shirts versus skins, but on the day of shooting, he explained, “I was kind of dividing it up, and very quickly found out that no one is looking to keep their shirt on. They were like, ‘No way, I worked too hard.’ ”

You can argue, correctly, that this is a sick way to treat the work of an actor, evidence of a greater sickness that has never left Hollywood. The actors, at least publicly, do not share your concern. In interviews, Glen Powell (Hangman), whose body is given pride of place in the new film’s montage, tells the story as comedy: that after they shot the football scene, the entire cast celebrated with a night of drinking and eating, finally free to indulge. And then they were told they were going to have to shoot the football scene again. “So then everybody, after the craziest night of tequila and tater tots and beer, we had to go back into the trenches and everybody’s back in the hotel gym doing crunches until they cried,” he told Uproxx. Even after they reshot the scene, Powell said, there remained a constant rumor around the set that they might shoot the football scene again. “So when you have that level of fear,” he said, “you make the right decisions in the kitchen.”

Obviously this is deranged, and Tom Cruise—the architect of Maverick, the person responsible in the grand scheme of things for its very existence and also for every minute detail contained within—is a nightmare. But Powell’s not wrong. This is, as Kosinski put it, “the Super Bowl of shirtless scenes,” and Powell was cast in this movie not only for his sparkling grin and his charming caddishness and his ability to withstand multiple G’s in a cockpit. He was cast because he would look incredible with his shirt off, standing on a beach, afternoon sun gleaming off his delts. Like a fighter pilot, he had a mission, and he accomplished it. (As Maverick includes a woman among its young guns—Monica Barbaro’s Phoenix—so too does its beach-sports scene, but Barbaro, who wears a sports bra and looks every bit the athlete as everyone else, does not get the kind of slo-mo close-ups her male co-stars do. “I mean, I worked my butt off, but I also got the sense very early on that like, this was not a moment for me,” Barbaro told the Wrap. “This was all about like, pecs and abs and oiled up men.”)

The thing that most surprised me about Maverick’s beach football scene was that it was, in fact, not at all extraneous. It occurs at a pivotal moment in the movie, when Maverick, now a teacher, is struggling to get the aviators he’s training for a secret mission to work together. So he has them play “dogfight football,” a game I believe to be wholly invented for this film, in which players use two footballs and both teams play offense and defense simultaneously. When Maverick’s commanding officer, played by Jon Hamm, demands to know why he’s wasting a valuable training day at the beach, Maverick points to the young guns hoisting mild-mannered navigator Bob (Lewis Pullman, occupying the Anthony Edwards role of designated shirt-wearer) on their shoulders in celebration. “You said to create a team,” Maverick says triumphantly.

I shouldn’t have been surprised. The contemporary action blockbuster is an efficient entertainment machine. Nothing is left to chance, and no cog within that machine remains unless it propels the machine forward. For all the damage that big-budget spectacle has done to Hollywood as a whole, it’s true that 21st century action cinema is more ruthlessly written, shot, and edited than the sometimes-junky, downright languorous action movies of the 1980s. Maverick may be about half an hour longer than Top Gun, but it’s as devoid of fat as those actors playing football, where Top Gun makes time for lingering shots of military hardware and sequences that land with a thud. (For instance, the gag before the beach volleyball sequence: “Slider … you stink.”) Of course the beach sports scene in Maverick would be not only oiled up but engineered perfectly to slot into the revving motor of the film.

[Read: Top Gun: Maverick Is the Year’s First Great Blockbuster.]

Yet watching Maverick’s dogfight football, I missed the feeling, so vivid in the original Top Gun, that this sequence of beautiful men performing their masculinity was meaningless, weightless, entirely separate from the plot. A perfect world of muscles, masculinity, camaraderie, beef. Facing a difficult scene, Tony Scott shot a music video and dropped it—inanely, delightfully—into the middle of a movie. It didn’t serve the story or the characters, really. It served us.

That’s not the case in Maverick, a much better movie than Top Gun, far smarter and more carefully crafted. For those exact same reasons, it’s much worse as softcore. The San Diego beach is gorgeously photographed. The actors, terrified into night after night of crunches, look fantastic. OneRepublic’s “I Ain’t Worried” is a perfectly brainless sequel to Kenny Loggins’ “Playing With the Boys.” But for all its professionalism, the scene won’t, I don’t think, take a new generation of viewers into the danger zone.