Last Updated on March 16, 2024 by Simon Abrams

“Now it’s dark, but I can see/Don’t you fuckin’ look at me/Now it’s dark, you’re gonna be/Exactly what I want to see.” –Anthrax, “Now It’s Dark” (1988)–

It’s 2022, and you can now buy special edition blu-rays of epochal Hong Kong shockers like Ebola Syndrome (1996) and The Untold Story (1993). In both true-crime style splatter pictures, Anthony Wong rapes, murders, and cooks his way through a slew of helpless victims. Both movies are mercilessly violent and inexhaustibly upsetting. They’re also maybe two of the most nihilistic horror-comedies you’ll see this side of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

Ebola Syndrome and The Untold Story now both look and sound better than they probably ever did. Their new home video releases (from Vinegar Syndrome and Unearthed Films, respectively) feature vital interviews and commentaries, including some conversations with Wong and Herman Yau, the latter of whom directed both movies.

Hardcore cultists used to primarily know these nihilistic genre movies from VCD and VHS bootlegs; there were also some officially licensed DVDs with variable AV quality. Now you can order high-quality blu-rays from online boutiques like DDDHouse and Diabolik DVD. In case you need further proof of our abidingly strange times.

When The Untold Story and Ebola Syndrome were first theatrically released, Yau’s unrepentant gross-outs were rated Category III, the Hong Kong equivalent of an X. That rating was established in 1988, four years after the American Motion Picture Association of America created the PG-13 rating and one year after the British Board of Film Classification’s “Video Nasties” panic. The Category III classification remains distinct from those other ratings since it produced a wave of popular exploitation pictures that targeted adult viewers, some of which were produced and/or distributed by major Hong Kong studios like Golden Harvest and Media Asia.

From 1988-1999, Category III titles made up 38-48% of theatrically released Hong Kong productions. (1) In 1992, Category III movies like Dr. Lamb and Naked Killer grossed a total of $159 million HKD ($43.8 million USD, after adjusting for inflation); in 1993, movies like Daughter of Darkness and Run and Kill added $185 million HKD ($46.5 USD today). (2) Category III ratings weren’t just for impotent serial killers and horny ghosts—movies about triad gangsters or anybody that threatened diplomatic relations with mainland China were also either taboo or subject to censorship.

Category III movies were a symptomatic last gasp for independent Hong Kong films, whose popularity had been waning for about a decade or more thanks to the rise of Cantonese-language TV programming and the burgeoning bootleg VCD market.

Category III movies afforded some filmmakers a limited sort of creative freedom while everybody waited to see just how much influence the mainland Chinese authorities—as well as film censors and producers—would have after the 1997 handover. And since Category III movies were mostly exploitative, many representative titles were essentially horror movies. Category III movies stoked Hongkongers’ manifold pre-handover anxieties: job insecurity, foreign neighbors, unaffordable or slum-like apartments, and promiscuity. Xenophobia and misogyny are a constant in these movies and, to a lesser extent, fears of the supernatural and undead. Category III movies were, in that sense, an accommodating umbrella genre that came to be defined by censorship, social criticism, fearful avoidance, and circular logic.

In the 1970s, the genre-bending work of Hong Kong filmmakers like Kuei Chih-hung helped to establish some formula-ready precedents for the Category III movies’ twin poles of gritty “social realism,” as Kuei put it, and “gimmicks”-driven fantasies. Shaw Brothers-produced hits like Kuei’s Hex (1980), Bewitched (1981), and their respective spinoff sequels—all of which are tenuously related to their predecessors—anticipated many Category III tropes, including an abiding preoccupation with black magic curses and spell-casting duels, often waged between Taoist monks and Thai occultists.

Kuei wasn’t the only inspiration for Category III horror movies like Beauty’s Evil Rose (1992), Devil’s Woman (1996), or The Eternal Evil of Asia (1995). Trends begat new or mutated trends, with or without auteur-related assistance; some other formative black magic titles include Shaw Brothers productions like Black Magic (1975) and Seeding of a Ghost (1983), the latter of which was retroactively graded Category III.

In a recent email, Hong Kong film expert Arnaud Lanuque writes that, while not all Category III directors were “Yes men who just did what they were told,” “they did work following a trend and under direct orders from their companies.” (3) Kuei, who directed some of the most committed/scuzzy Hong Kong horror movies of the 1970s and 1980s (see: Corpse Mania, Killer Snakes, and Spirit of the Raped), was also characteristically blunt about why he never made the same horror movie twice. “To please the audience, you must resort to gimmicks. I make fantasy movies because audiences like them.” (4)

Many Category II-rated horror movies, like the zombie cop comedy The Blue Jean Monster (1991) or the retroactively graded possession flick Devil Fetus (1983), tiptoed up to the same limits of bad taste that more extreme Category III movies flopped over. Foreigners, rapists, and sex workers proliferated in Category III movies, and fear was in the air. Violent crime either rose or fell depending on who you trusted: a 1992 report from The British Journal of Criminology says that violent crimes actually diminished since the 1980s, given under-reporting in that decade (5); a Los Angeles Times article from 1990 insists that violent crime was on the rise, but the port city’s murder rate was down. (6)

Category III expert Mike Leeder emphasizes the well-publicized triad gang-related violence that captured the imagination of both news readers and Category III audiences. (7) Lanuque suggests that Hong Kong residents were more susceptible to fears of crime after the 1980s: “Hong Kong people got used to feeling secure fairly quickly, especially feeling safe at night[…]and because of this feeling of security, the violent cases became even more impactful for the public.” (8)

Ghost comedies and black magic potboilers also distracted jaded Hong Kong residents with Freudian shell games since, as Sévéon writes, “Bad luck charms and other possessions are, in fact, rarely the work of Hongkongers, but much more generally sinister individuals from Southeast Asia.” (9)

With all this in mind, it’s not surprising that Category III horror movies were not united by any general narrative formula or stylistic qualities. Despite their mutual exoticism and concern with black magic, The Eternal Evil of Asia is a winking low-brow horror-comedy about a bachelor party gone very wrong, while The Seventh Curse (1986) is an earnest but crazed action-fantasy (imagine an even more brain-damaged Temple of Doom). Even the goony slapstick of The Eternal Evil of Asia is a different kind of silly than the horny comedy of Jail House Eros (1989), a women-in-prison flick set in a haunted and overcrowded penitentiary. And while sex consistently sold better than violence, horror and fantasy elements were just one color on the Hong Kong exploitation filmmaker’s unwashed palette.

Ghosts and black magic still occasionally cropped up in 21st-century Hong Kong productions, like the grim throwback Gong Tau: An Oriental Black Magic (2007) or the broad ghost comedy Coffin Homes (2021). And while American cultists continue to discover Category III classics thanks to the diligent curation of home video vendors like Sloppy Second Sales and Diabolik DVD, recent Hong Kong productions, like the arty true-crime thriller Limbo (2021) and the exuberant screwball noir Detective Vs. Sleuths (2022) feel like tortured love letters to Category III movies.

It’s also worth noting that Category III movies continue to resurface even after the mainland Chinese government passed the National Security Law in June 2020. Lanuque recently told me that the National Security Law could potentially lead the extant Hong Kong film industry to a “de facto” reversion to “mainland censorship guidelines.” (10) That loss of creative autonomy isn’t new news though, since the Hong Kong film industry is already bound to the tastes of mainland audiences.

Still, Category III cinema was always an expression of Hongkongers’ “self-censorship,” as Sévéon writes, since “the disappearance of the most savage genre of HK cinema is partly linked to economic censorship from China.” (11) For example: “Black magic is one of the big no-nos for Mainland China censorship,” Sévéon added in a recent email. (12) “Unsurprisingly, only a handful of black magic films have been produced since 1997.” The bad old days are back, and now, so are the noisy ghosts of Hong Kong’s pre-Handover past.

I tend to agree with Sévéon when he notes that Category III movies were “a last desperate attempt to prove to Hongkongers that they are free and alive.” (13) I also think it’s easy to misremember how conflicted and self-defeating a lot of Category III movies were, given their uneasy mix of social commentary and political scapegoating. This limited column will hopefully help orient horror fans as they either start or continue to dig into Category III movies.

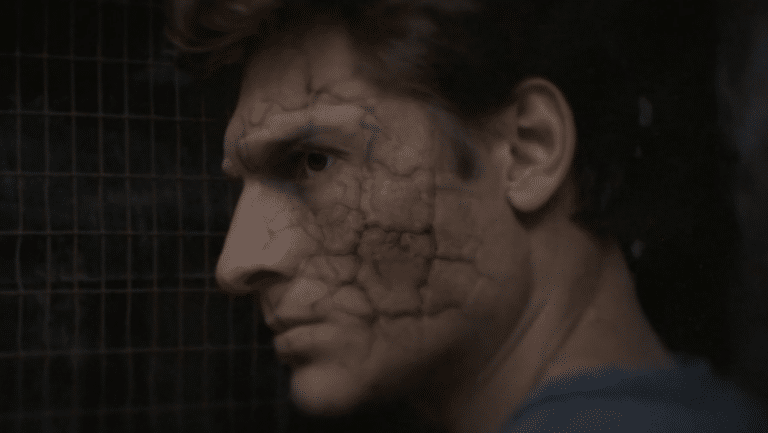

Up next: a profile/tribute to The Untold Story star Anthony Wong.