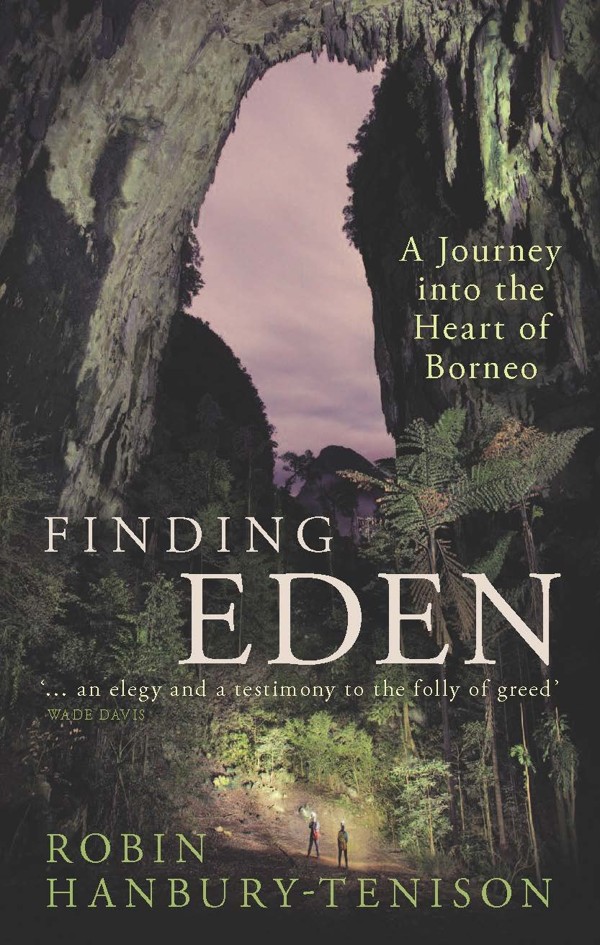

Review | Book review: Finding Eden tells of Borneo’s beauty before deforestation destroyed the island

In detailing his 1978-79 expedition of Borneo to study the remote Penan tribal people, English explorer Robin Hanbury-Tenison laments how a pristine paradise has since been utterly destroyed by loggers and palm oil plantations

Finding Eden: A Journey into the Heart of Borneo

by Robin Hanbury-Tenison

I.B. Tauris

3.5 stars

Borneo was once a byword for paradise, but the formerly pristine island in Southeast Asia’s Malay Archipelago now lies in ruins, mostly due to destruction caused by the logging industry.

The island is shared by the Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak, Indonesian Kalimantan and the tiny nation of Brunei. Sarawak – in the giant island’s northwest – has lost more than 90 per cent of its lowland primary forests, despite protests by environmentalists.

Indonesian villagers cut down forest to plant palm oil in orangutan sanctuary

“Opposition to the phenomenal rate of logging in Sarawak grew during the 1980s and 1990s but, in spite of massive international interest and campaigning, nothing changed,” English explorer Robin Hanbury-Tenison writes in his politically charged travelogue Finding Eden: A Journey into the Heart of Borneo.

“In fact,” says the author, “things got much worse as palm oil became the most widely used vegetable oil on the planet and the highly lucrative industry boomed. While leaving only secondary forest behind after all the larger trees have been removed would be bad enough, converting the land into sterile plantations has been a catastrophe.”

Even worse, he writes, is that most of the remaining forested areas have now had roads carved into them, ominous red scars that indicate preparations are underway to invade the last, most inaccessible zones.

The holder of an OBE, among other honours, Hanbury-Tenison is president of Survival International, a tribal support group he cofounded in 1969. From 1978 to 1979 he led a 15-month expedition through Borneo’s jungle to study the remote Penan tribal people. Supported by Sarawak’s government and involving more than 100 scientists, it is one of the largest ever expeditions mounted by the UK’s Royal Geographical Society.

He describes it as the expedition that kick-started the global rainforest protection movement. It showed that species-rich rainforests, or “the lungs of the earth”, were key to our survival, and a detailed account of the journey forms the bulk of Finding Eden.

Little did Hanbury-Tenison know that the notes he took on his journey would read like a swansong for Borneo and its ethnic people. In line with Borneo’s ecological demise, the Penan tribe was also set to suffer.

The tragedy is that their lifestyle was potentially sustainable. “The huge wealth of the country could have been exploited sustainably and in a manner that benefited all in the long run, and not just filled a few obscenely fat Swiss bank accounts,” writes Hanbury-Tenison, whose previous works include the travel writing anthology The Oxford Book of Exploration.

When Hanbury-Tenison returned to Borneo two decades after his expedition, he found that his closest Penan contact, Nyapun, had served time in prison for trying to stop construction of a road.

Naively, he writes, Nyapun had hoped to negotiate with the authorities. “I wanted to make sure there would be a place for my family and descendants, but they said they wanted everything. They were going to log the whole area,” Nyapun says.

The dream weavers of Sarawak, headhunters once, fight to save their art and their traditional way of life

Across Borneo, the book shows, the logging sector has played a zero-sum game and treated locals like savages. Now their once diverse homeland is overrun by the sterile crop Hanbury-Tenison abhors: palm oil.

Palm oil is used in a range of goods including lipstick, ice cream and detergent. But once our global passion for palm oil products ends, as Hanbury-Tenison says it will, the land will never recover, because the crop’s impact is terminal.

The aggressively cultivated land seems to have fared much better in colonial times. The book quotes forestry expert Robb Anderson as saying that during the 1841-1946 reign of the British Brooke rajas, harvesting was done sustainably. Just 1 per cent of the national forest was logged each year, then carefully restored and allowed to regrow.

After independence, however, increasing pressure was brought on the elected government to grant larger concessions – often to foreign timber companies. Massive bribes helped seal the deals. “Many good babies have been thrown out with the dirty colonial bathwater,” Hanbury-Tenison writes.

Finding Eden reads like a cross between an adventure yarn and an exposé with great emotional grunt. One niggle is that much of the story is told through diary entries. The terse references to downpours, ablutions and centipedes grow monotonous, but Hanbury-Tenison may be right to stick with the format, given his expedition’s historical clout.

Either way, he comes across as incredibly positive. For him, Bornean longhouse lodging evokes life’s essential poetry, magic, mystery, joy and wonder.

“Death and accidents do occur, of course, but until then everyone knows from childhood how to survive and enjoy life without any outside help. Whatever is needed can be made by anyone. There is food all around and materials for shelter. This is something we have lost,” he writes.

Malaysian DJ samples indigenous music to spread land rights message in Sabah, hit by deforestation

The 288-page book also addresses the folly of greed and raises the question of who the real savages are. Hanbury-Tenison explains that it is certainly not the Penan, who live at one with nature. Instead it is those whose policy of pillage – slyly framed as “development” – only victimises the island’s original stakeholders.