Just after midnight on 2 December 1984 a storage tank at the Union Carbide chemical plant in Bhopal began leaking a gas called methyl isocyanate (MIC). The plant, in Madhya Pradesh, India, was equipped with six safety systems designed to detect such a leak, none of which were operational that night. Twenty-seven tons of MIC gas spread throughout the sleeping city.

As an engineer was flushing water through a corroded pipe in the MIC production complex, a series of valves failed, allowing the water to flow freely into one of the three-storey tanks holding the toxic chemical in a liquid state. This caused a rapid and violent reaction. The tank shattered in its concrete casing and spewed a deadly cloud of MIC, hydrogen cyanide, monomethylamine and other chemicals, all of which hugged the ground.

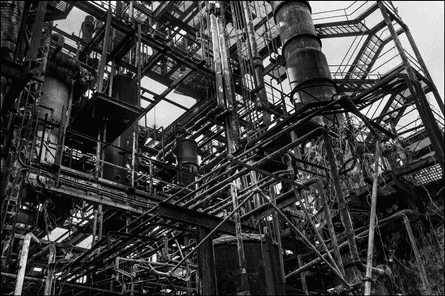

The derelict Union Carbide plant sits on a 20-hectare (49-acre) site in Bhopal’s old town

As the toxic cloud blanketed much of Bhopal, people began to die. Aziza Sultan, a survivor, remembers: “At about 12.30am, I woke to the sound of my baby coughing badly. In the half-light, I saw that the room was filled with a white cloud.

“I heard a lot of people shouting. They were shouting ‘Run! Run!’,’ she says. ‘Then I started coughing, with each breath seeming as if I was breathing in fire. My eyes were burning.”

Champa Devi Shukla recalls: “It felt like somebody had filled our bodies up with red chillies; our eyes had tears coming out, noses were watering, we had froth in our mouths. The coughing was so bad that people were writhing in pain.

“Some people just got up and ran in whatever they were wearing, or even if they were wearing nothing at all. People were only concerned as to how they would save their lives, so they just ran.”

In those apocalyptic moments, no one knew what was happening. People started dying in the most hideous ways. Some vomited uncontrollably, went into convulsions and dropped dead. Others choked, drowning in their own body fluids.

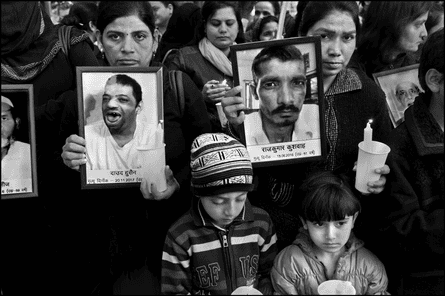

Staff from the Sambhavna clinic hold a vigil in memory of victims. It was built with funds raised in 1994 by the Bhopal Medical Appeal, which appeared in the Guardian and Observer on the disaster’s 10th anniversary. The clinic has treated more than 65,000 people and nearly half of the 55 staff are gas survivors

Many people died in the stampedes through narrow alleyways where street lamps, swamped in gas, burned brown. The crush of fleeing crowds wrenched children’s hands from their parents’ grasp. Families were literally ripped apart.

MIC, used in the production of pesticides, is highly corrosive if inhaled. Half a million people were exposed and at least 25,000 have died as a result. More than 150,000 people still suffer from disorders caused by the accident and the subsequent contamination – respiratory diseases, kidney and liver disorders, cancers and gynaecological issues.

No one knows exactly how many thousands of people died. Union Carbide put the number at 3,800. Municipal workers who collected bodies, loading them on to lorries to be buried in mass graves or burned on funeral pyres, say they handled at least 15,000 corpses. Based on numbers of burial shrouds sold in the city, survivors make the conservative claim that about 8,000 people died in the first week alone. But the dying has never stopped.

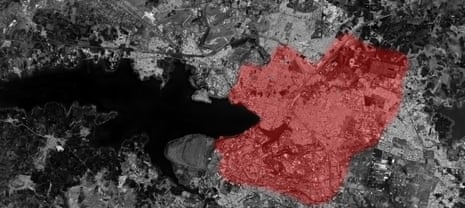

A satellite map of Bhopal, showing the extent of the toxic gas cloud, which affected half a million people

Rashida Bi, a survivor who has lost five members of her family to a variety of cancers over the past three decades, considers those who escaped with their lives “the unlucky ones”. She adds: “The lucky ones are those who died on that night.”

Union Carbide shut down the site and left it to rust. It has never been cleaned up and so the poisoning continues. In 1999, testing of groundwater and well-water near the site revealed mercury levels up to 6m times greater than what is accepted as safe by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Images showing the plight of the survivors and their children. Many children of local people, whose drinking water was contaminated, were born with developmental issues. Among survivors, respiratory ailments are widespread

Chemicals were found in the water that cause cancer, brain damage and birth defects. Trichloroethene, a chemical shown to impair foetal development, was found at levels 50 times higher than EPA limits. Testing published in a 2002 report revealed poisons such as 1,3,5-trichlorobenzene, dichloromethane, chloroform, lead and mercury in women’s breastmilk.

In 2001, the Michigan-based Dow Chemical Company bought Union Carbide, acquiring its assets and liabilities. Dow, however, has steadfastly refused to clean up the Bhopal site. Nor has it provided safe drinking water, compensated the victims or shared with the Indian medical community any information it holds on the toxic effects of MIC.

The data that Bhopal’s doctors have requested, and say they need in order to deal with the lasting effects of the crisis, Dow has treated like a trade secret and held back.

Vimla Sahu, who lives near the abandoned Union Carbide plant, cannot conceal her anguish

Union Carbide built the Bhopal factory in the 1970s, confident that India represented a huge untapped market for its pesticides. However, sales never met the company’s expectations. Indian farmers, struggling to cope with droughts and floods, lacked the money to buy Union Carbide’s products.

For 15 years before the disaster, Union Carbide routinely dumped highly toxic chemical waste at sites inside and outside the factory.

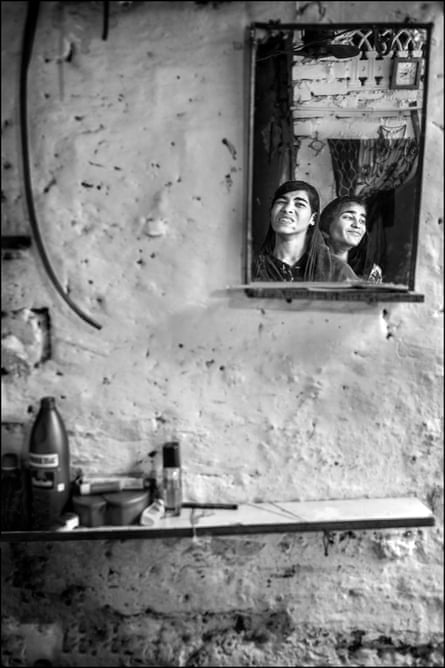

Twin sisters Shazia and Fouziya in their home in the Nawab area of Bhopal, near the factory, where toxins leaked into the water supplies. They both have severe mental development issues, which doctors believe was due to genetic damage

Thousands of tons of pesticides, solvents, chemical catalysts and byproducts lay strewn across six hectares (16 acres) inside the plant. Evaporation ponds covering 14 hectares outside the factory were filled with thousands of litres of liquid waste.

The plant, which never reached its full production capacity, proved to be a loss-making venture and was shut down in the early 1980s, though large quantities of dangerous chemicals were left abandoned on the site.

Three huge steel tanks continued to hold more than 60 tons of MIC. Although MIC is a particularly unstable gas, Union Carbide’s elaborate safety systems were allowed to fall into disrepair and become ineffective. The factory managers’ reasoning seemed to be that, since production had stopped, no threat remained.

As monsoons battered the decaying plant, rain caused the chemical-waste evaporation ponds to overflow. Toxins penetrated the soil, leaching into underground channels. Contaminated water from wells was pumped into 42 neighbourhoods.

In secret tests carried out by Union Carbide in 1989, the results of which were subsequently seen by the Bhopal Medical Appeal, the company concluded that the site was lethally contaminated. Groundwater instantly killed fish. Many of the places where the samples were taken were just inside the factory wall – people drew their water from wells and standpipes on the other side of the wall.

A gas-affected patient undergoes Panchakarma steam treatment, a traditional Ayurvedic therapy, at the Sambhavna clinic. The clinic describes its approach to treating survivors of the disaster as ‘offering drug-free therapies for chemically burdened bodies’

Despite having indisputable proof of the site’s toxicity, Union Carbide chose not to notify local people that the water was unsafe. It attacked those in the community who voiced concern, dismissing them as “troublemakers”.

The full extent of the contamination was not exposed until 1999, when Greenpeace investigators, after running a series of tests, reported that soil and water in and around the plant were contaminated by organochlorines and heavy metals, which are both highly toxic and accumulate in the body.

A follow-up study in 2002, which found mercury, lead and organochlorines in the breastmilk of women living near the plant, also discovered that the children of gas-affected women suffered an array of debilitating illnesses, including birth defects and reproductive disorders.

The “polluter pays” legal principle applies in India but Union Carbide and its parent company, Dow, have refused to pay compensation for this second environmental catastrophe of contaminated water.

A boy drinks water from a hand pump near the plant. Water samples taken in and around the factory were found to be highly contaminated by organochlorines and heavy metals

In 1989 Union Carbide, in a partial out-of-court settlement with the Indian government, agreed to pay $470m in compensation to the victims of the disaster. But the victims themselves were not consulted in the negotiations, and more than nine in 10 received a maximum of $500 each, or enough to pay medical expenses for five years.

Today, victims of the disaster eke out a perilous existence. More than 50,000 Bhopalis are unable to work because of their injuries. Many have no family left at all.

In 1991, India’s criminal justice system charged Warren Anderson, Union Carbide’s chairman and chief executive at the time of the disaster, with “culpable homicide not amounting to murder”. If he had been convicted in India, he would have faced a maximum of 10 years in prison. Anderson never stood trial. An Indian extradition request languished in the US courts for three and a half years without a response from officials.

In September 2014, a few months before the 30th anniversary of the disaster, Anderson, the son of a Brooklyn carpenter, died aged 92 in a nursing home in Vero Beach, Florida.

Doctors at the Chirayu cancer hospital in Bhopal examine a patient from one of the neighbourhoods around the abandoned plant

Union Carbide was charged with culpable homicide. The corporation, like its former chief executive, refused to face trial in India, and the charges have never been resolved.

Dow and Union Carbide merged in 2001. The agreement submitted to regulators omitted any mention of pending criminal cases against Union Carbide. Dow has been served summons to appear in court at least six times in Bhopal to explain Union Carbide’s continued absence. It has ignored all six notices.

Union Carbide remains liable for the environmental devastation it caused. Environmental damages were not addressed in the 1989 settlement, and the contamination continues to spread; these liabilities became the responsibility of Dow.

Some Dow shareholders tried to stop the merger, knowing that a corporation assumes the assets and the liabilities of a company it buys, according to established corporate law. Indeed, soon after it acquired Union Carbide, Dow settled a US lawsuit, paying out $2.2bn to compensate people in the US affected by Union Carbide’s use of asbestos in legacy products. But Dow maintains that it is not liable for Union Carbide’s actions in Bhopal.

Tim Edwards is executive trustee of the Bhopal Medical Appeal.

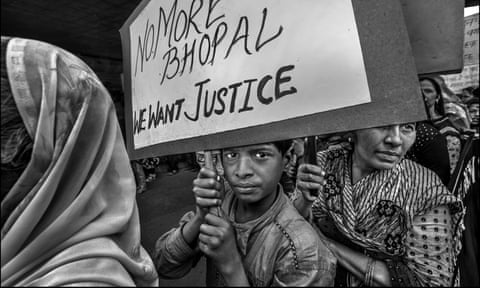

Demonstrators marching through the streets of Bhopal to mark the 34th anniversary of the Union Carbide gas disaster in 2018